Tales of old Gerringong corn growing

Mark Emery

16 September 2025, 1:00 AM

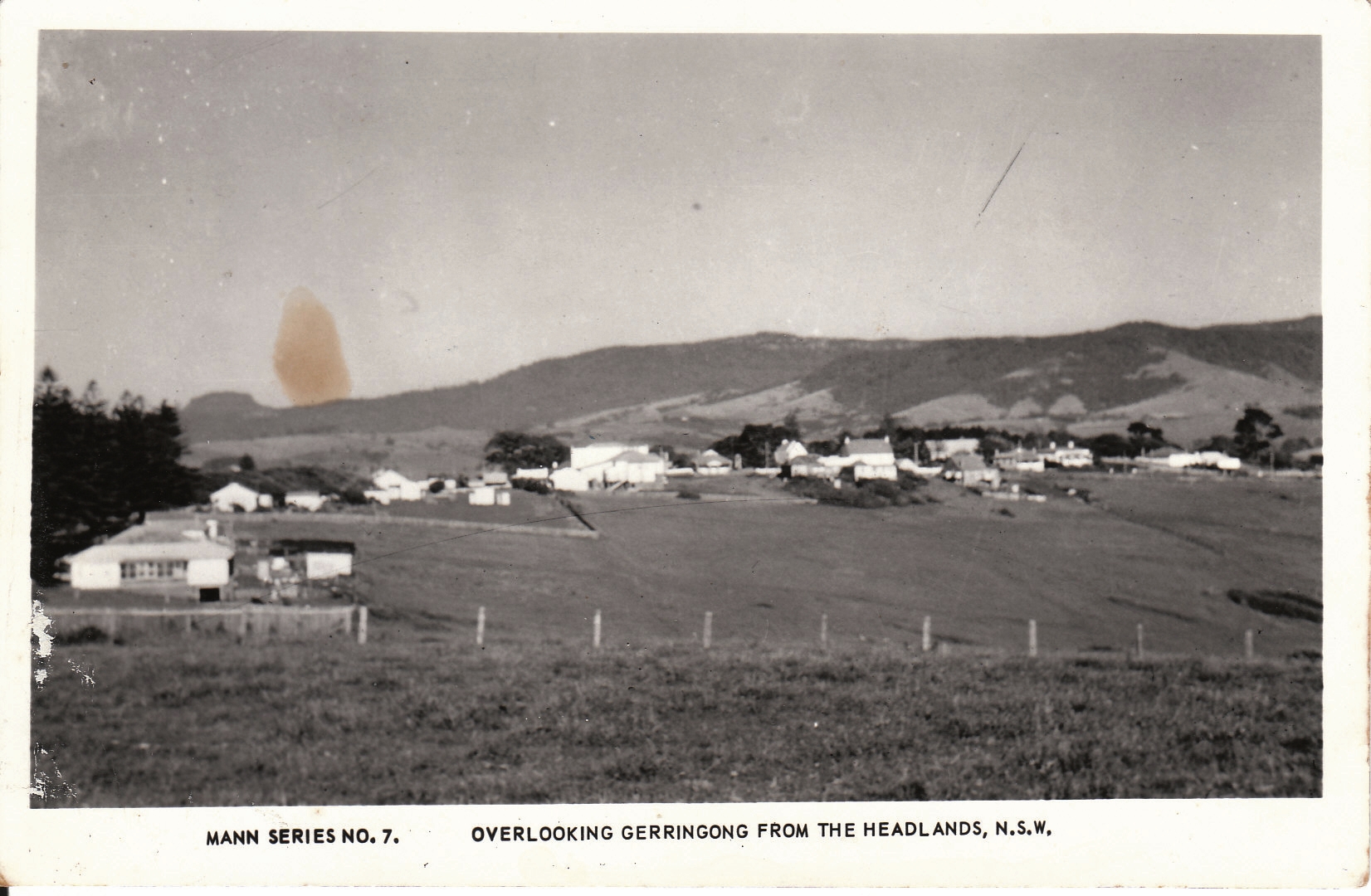

Postcard of Gerringong from the headland.

Postcard of Gerringong from the headland.As a child I can vaguely recollect my father growing corn. My sister Merelyn confirmed this by saying he grew corn at Gerroa to feed the cattle. But the growing of corn was very important for farmers many years before that. Clive Emery wrote a tale about his father growing corn at Foxground.

For as long as my Dad lived, corn was his favourite crop.

Never a season went by without us having acres of maize growing in our best paddocks.

Hickory King was Dad's favourite grain. I never did discover how many years he had grown this variety, but every year throughout my young life that was the variety grown.

Dad supported this variety because he said Kellogs used it to make Corn Flakes, so it must be the best! Rightly or wrongly, it was the favourite - that was until Cliff and I decided to try some of the new varieties coming on the market.

I honestly believe it was the grain he grew as a boy, and saved the seed each year to keep it pure.

He said when he went to the North Coast, an old farmer gave him some advice which he heeded well throughout his life.

“Emery,” the old fellow said, “always make sure you have some corn in the barn. In bad times, my kids were crying round the table and there was nothing to eat, but the missus ground the corn and made gruel and baked to fill their little bellies! We have lived on corn for weeks on end, when there was no money to buy food!”

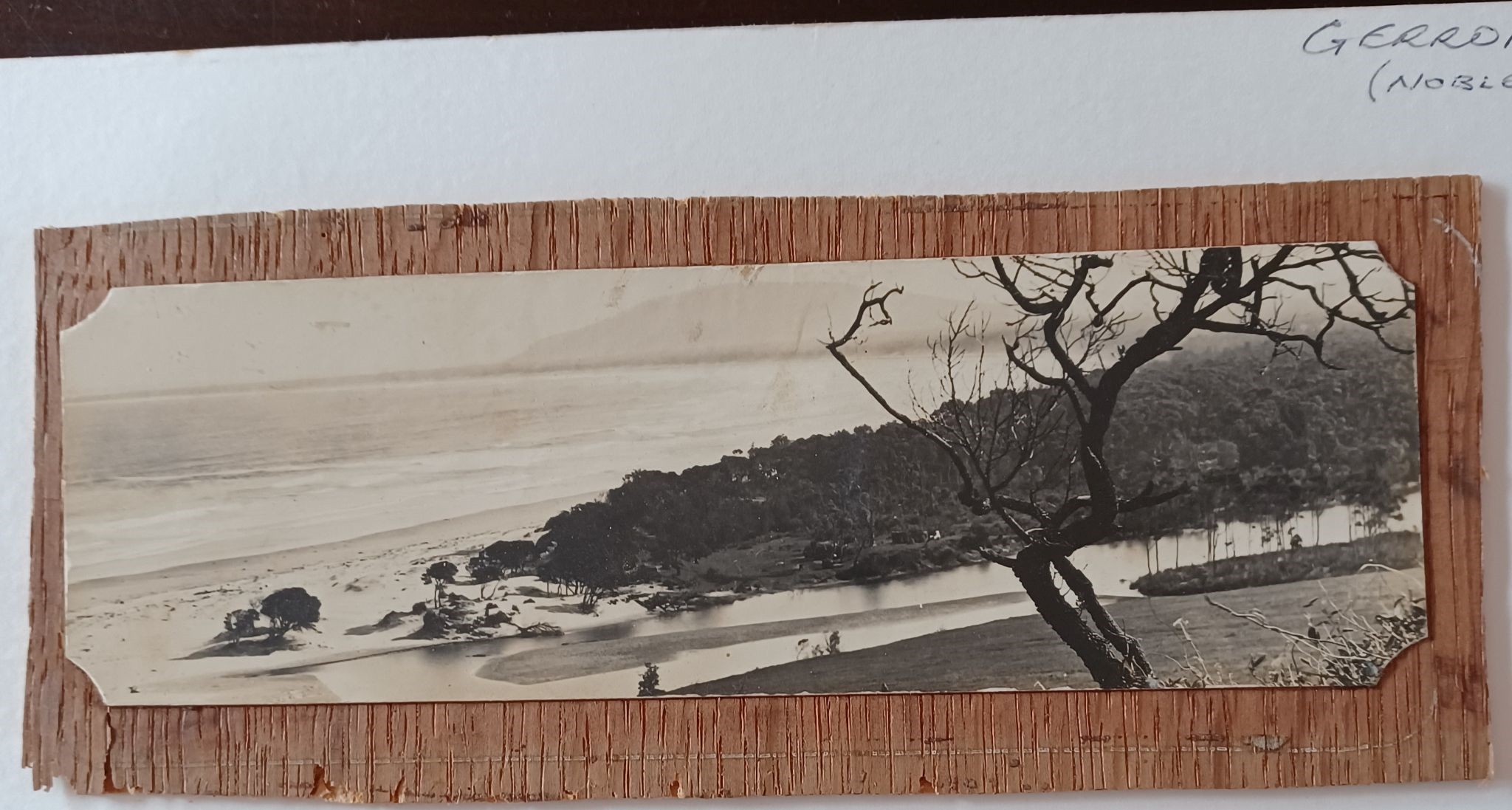

Gerroa, many years ago.

The sincerity of this declaration was so real Dad took it to heart and it may have been the trigger which energised him to carry it out.

Whatever, 80 years since that remark I am still growing maize!

I was sorry for Dad's sake when we changed the breed to Giant White because of its superior cropping potential over Hickory King - the cobs of which we learned first to husk as boys.

There was something about family husking bees when we all sat under a hurricane lamp in our barn husking the cobs until our little heads began to nod, and Dad told us stories of his life until all we wanted to do was curl upon his lap and be buried in husks!

He would pick the two of us over his strong shoulders and carry us off the bed.

The hempen bags we used for collecting the corn cobs had many uses on the farm; used often for overcoats during inclement weather or for bagging the potato crop in season and in many homes used for bedding, then called a "Wagga Rug'.

The peculiar thing about corn is that every animal on our farm liked it.

The cows were fed corn in the stalls, the pigs in their pens, the horses in their nosebags, the dogs and old Joe the cat, and of course so many birds.

Corn was a staple food for the fowl as a matter of course - ground for the chicks and cracked for their mothers.

The crows, the Rosella Parrots, the White Cockatoos would raid the crop in the paddock.

Dad stood a Scarecrow at the end of the paddock to frighten them away. It was so lifelike that our neighbour rode down one day to have a yarn to the fellow standing at the edge of the crop.

But the birds were wiser than he thought - they moved to the other end of the paddock for their meal of corn.

My mother would come to the barn some nights to help with the husking. She did not use a husking-peg like the rest of us but tore the husks off with her hands; it was good to have Mum there because she could tell stories too.

She did not know much about corn until she married Dad, because the property she was raised on did not lend itself to ploughing and cropping as it was so steep.

We usually retired about ten at night, when we would hang our husking pegs on a nail and carry the husks out to the paddock where the herd was waiting to chew on them.

We often had wrestling bouts in the pile of husks for fun. We piled our barn lofts with cobs, to be left there to dry before being ground for the cattle.

When we moved to Foxground, nothing changed. For years we went on with the husking bees, with this difference.

Mother and Olive made it into a Valley night picnic and so many young folk came to help and have fun in the barn, while their mothers stayed with Mum in the house.

But they were not idle - we all shook the corn hairs and dust from ourselves and enjoyed the repast our mothers had prepared.

They were happy events, and many a lass was grabbed for a roll in the pile of husks before the night was over, and released in time to prevent being smothered.

Graveyard at Gerringong about 70 years ago.

In the dim light of the hurricane lamp nobody knew who was rolling who, nor did anyone care, and everyone was happy and joyous laughter filled the barn.

It was during the husking bees I learned that cobs of corn always had even rows of grain, and Dad offered anyone 10 shillings if they could bring forth a cob with uneven rows.

He found it was counter-productive for we counted the rows on each cob before tossing it into the heap and husking less cobs. No one got the money, however.

Why we didn't husk the cobs in the paddock was never really explained. When I began farming on my own that is what I did - it meant less handling - but Dad always seemed to have plenty of labour.

It is strange how we stick to the old routine at times until a total stranger will correctly make a suggestion.

Up until then it was a matter of: 'if it was good enough for my father it is good enough for me!'

Somehow, I am glad to be able to tell of the simple fun we had at our husking bees. Thinking it over, I wouldn't have missed it for the world !

As Hickory King was laid aside, so has the plough and Cydesdales that pulled it. Where we used to walk nine and a half miles behind the plough to turn an acre of furrows, with the tractor we did that before breakfast.

The steel machine that made it possible did not rub its head on your chest, nor nuzzle your shoulder as you exchanged winkers for nosebags, nor do you pat it on the shoulder.

Strangely, mechanisation has not kept the farmer in the field, and houses are growing where once they trod! The art and science of farming is dying.

NEWS